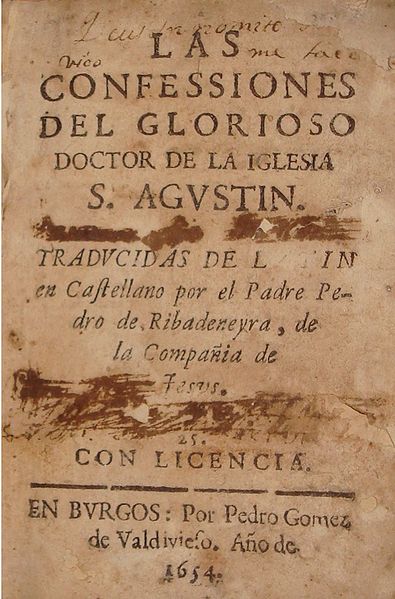

The Confessions of Augustine's Life

Series | Repentance

Augustine wrote the Confessions when he turned 43, covering the first 33 years of life leading up to his conversion. He intended it to be much more than an autobiography. He explained in his Retractions (written near the end of his life around AD 426/427 to correct or annotate his previous works),

Augustine wrote the Confessions when he turned 43, covering the first 33 years of life leading up to his conversion. He intended it to be much more than an autobiography. He explained in his Retractions (written near the end of his life around AD 426/427 to correct or annotate his previous works),

The thirteen books of my Confessions whether they refer to my evil or good, praise the just and good God, and stimulate the heart and mind of man to approach unto Him.

The entire book is a prayer to God, and contains, as we would suspect based on the title, confessions of his sin. But unlike so many modern self-absorbed testimonies, Augustine is not the hero, or even the main character of the story. He portrayed himself as wicked and in need of help. When he found himself doing well, he directed the credit away from himself. For example, he encouraged his friend Darious in a letter (AD 429),

Accept the books of my Confessions which you have asked for. Behold me therein, that you may not praise me above what I am….If there is anything in me that pleases you, praise with me there Him whom I wish to be praised for me–for that One is not myself. Because it is He that made us and not we ourselves; nay, we have destroyed ourselves, but He that made us has remade us.

The Confessions were, therefore, primarily about God, not Augustine.

[It is the very purpose of this book] to give the impression that Augustine himself was a weak and erring sinner, and that all of the good that came into his life was of God…this whole account of his life history…up to its crisis in his conversion is written…not that we may know Augustine, but that we may know God: and it shows us Augustine only that we may see God. (BB. Warfield, Studies in Tertullian and Augustine, vol. 4 in The Works of Benjamin B. Warfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1920; reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1991) 267).

Not only does Augustine’s depravity unfold, but also his intimate love for God emerges in little phrases like, “God of my heart,” “God my sweetness,” “[God] my late joy.” (Brown, 167) The Confessions narrate the change in Augustine’s heart (Brown, 169), and exhibit the enormous difference between confessions that focus on God and confessions that focus on self.

On the first page of Confessions, he swiftly and succinctly summarized man’s greatest joy, and the reason why men so often fail to experience that joy.

You stir man to take pleasure in praising You, because You have made us for Yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in You. (I. i.)

Men are made by God to worship Him, not out of duty, but for their delight. The Confessions are Augustine’s personal testimony of his restless heart’s journey to that delight in God. It is the story of empty, yet enslaving sinful pleasures that kept him from the greatest pleasure, God. It recounts the increasing misery and unhappiness of his soul with “ferocious honesty” (Brown, 171).

As he grew from infancy into boyhood, he noted:

I myself was meanwhile dying by my alienation from You, and my miserable condition in that respect brought no tear to my eyes. (I. xii.)

He had heard the truth, but he preferred “seductive delights” (I. xv.). He understood that it was part of God’s judgment to let men remain in blindness: “By Your inexhaustible law You assign penal blindness to illicit desires” (I. xviii.). Yet the Lord disciplines those He loves. “There can be no surprise that an unhappy sheep wandering from Your flock and impatient of Your protection was infected by a disgusting sore” (III. iii.).

But he still could not escape his lust. “The single desire that dominated my search for delight was simply to love and to be loved” (II. ii.).

I was in love with love, and hated safety and a path free of snares….I was without any desire for incorruptible nourishment not because I was replete with it, but the emptier I was, the more unappetizing such food became. So my soul was in rotten health. (III. i.)

Sin makes a man stupid. Even though the further one moves away from God, the more miserable he becomes, he also becomes less interested in returning to God. God gave Augustine what he (thought he) wanted in order to make him more miserable.

I aspired to honors, money, marriage, and You laughed at me. I those ambitions I suffered the bitterest difficulties; that was by Your mercy–so much the greater in that You gave me the less occasion to find sweet pleasure in what was not You. (VI. vi.)

I was full of my punishment, but I shed no tears of penitence. (VII. xx.)

God was systematically showing him what sin really looks like.

You took me up from behind my own back where I had placed myself because I did not wish to observe myself, and You set me before my face so that I should see how vile I was, how twisted and filthy, covered in sores and ulcers. And I looked and was appalled, but there was no way of escaping myself. If I and You once again placed me in front of myself; You thrust me before my own eyes so that I should discover my iniquity and hate it. I had known it, but deceived myself, refused to admit it, and pushed it out of my mind. (VIII. vii.)

He was a slave to his sin until God delivered him in Milan. At the end of August, 386, he and a small group of friends hosted a Christian man, Ponticanus, who told Augustine and his friend Alypius about the monks in Egypt and of their founder, Saint Anthony. While Augustine listened, his heart burned with guilt and he withdrew into a garden beside the house. The following is one of the most memorable testimonies in church history.

He was a slave to his sin until God delivered him in Milan. At the end of August, 386, he and a small group of friends hosted a Christian man, Ponticanus, who told Augustine and his friend Alypius about the monks in Egypt and of their founder, Saint Anthony. While Augustine listened, his heart burned with guilt and he withdrew into a garden beside the house. The following is one of the most memorable testimonies in church history.

I threw myself down somehow under a certain fig tree, and let my tears flow freely. Rivers streamed from my eyes, a sacrifice acceptable to You, and (though not in these words, yet in this sense) I repeatedly said to You: ‘How long, O Lord? How long, Lord, will You be angry to the uttermost? Do not be mindful of our old iniquities.’ For I felt my past to have a grip on me. It uttered wretched cries: ‘How long, how long is it to be?’ ‘Tomorrow, tomorrow.’ ‘Why not now? Why not an end to my impure life in this very hour?’

As I was saying this and weeping in the bitter agony of my heart, suddenly I heard a voice from the nearby house chanting as if it might be a boy or a girl (I do not know which), saying and repeating over and over again, (Tolle lege, tolle lege) ‘Pick up and read, pick up and read.’ At once my countenance changed, and I began to think intently whether there might be some sort of children’s game in which such a chant is used. But I could not remember having heard of one. I checked the flood of tears and stood up. I interpreted it solely as a divine command to me to open the book and read the first chapter I might find….So I hurried back to the place where Alypius was sitting. There I had put down the book of the apostle when I got up. I seized it, opened it and in silence read the first passage on which my eyes lit: ‘Not in riots and drunken parties, not in eroticism and indecencies, not in strife and rivalry, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ and make no provision for the flesh in its lusts’ (Romans 13:13-14).

I neither wished nor needed to read further. At once, with the last words of this sentence, it was as if a light of relief from all anxiety flooded into my heart. All the shadows of doubt were dispelled. (VIII. xii.)

God can even use the “bulls’-eye” approach to Scripture reading. God granted him repentance and faith brought peace to his previously restless heart.

You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, You put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath and now pant after You. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for You. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is Yours. (X. xxvi.)