Combing Hair at Thermopylae

On the first day Evangel Classical School met for classes I read the following quote from C. S. Lewis during my convocation address.

If we let ourselves, we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work. The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavourable. Favourable conditions never come.

I had seen that quote in a few places, most applicably on the back cover of a book about classical Christian education. I quoted it to comfort those of us with more butterflies than boldness. It’s similar to the panic a rookie teacher might feel upon opening a fresh box of dry erase markers to find that none of them came with caps; would we open a school only to squeak out a faint mark? Our circumstances, while certainly not the worst they could have been, were not favorable. We were far from bouquets of newly sharpened pencils, or even from knowing which brand of pencil sharpener would survive for more than a week. We aspired to this noble task, though having more zeal than knowledge doesn’t always work out so well. We all know more than we did then—thank God—and that includes knowing that classical Christian education is an indispensable burden. We want it even more badly now.

Since that opening of opening days I have read Lewis’ quote in its native paragraph. He used those lines in an address titled “Learning in Wartime.” You can find it for free online or in a collection of Lewis’ articles called The Weight of Glory.

In his address Lewis raised and replied to a question about the legitimacy of study—especially study of the liberal arts—while in the middle of a war. It was October, 1939, and World War II was less than two months old. From the location of Lewis’ lectern in Oxford, England, his listeners were more than academically concerned.

[Every student] must ask himself how it is right, or even psychologically possible, for creatures who are every moment advancing either to Heaven or to hell to spend any fraction of the little time allowed them in this world on such comparative trivialities as literature or art, mathematics or biology. If human culture can stand up to that, it can stand up to anything.

Lewis argued from the greater to the lesser. He showed that Christians believe that death is always only one step away and that Heaven or hell await. A war reminds us of our upcoming death but it does nothing to increase the chance of our death. We have always been going to die.

The vital question is not whether learning in wartime is defensible but whether learning during any of our time on earth is. If teachers can, if teachers should, sow seed in the scholastic field with eternal reward or eternal punishment on the other side of the fence, then teaching and learning is appropriate when nations fight over a portion of the field.

Lewis observed that God gave men an appetite for knowledge and beauty. Want of security has never stopped the search, otherwise “the search would never have begun.” Instead,

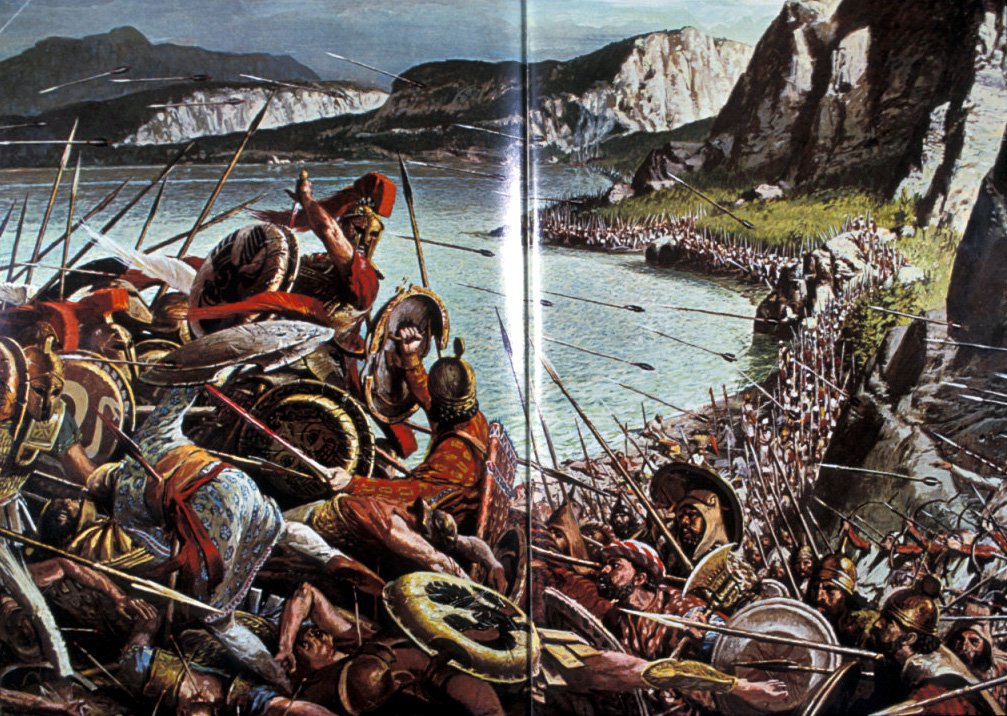

[Men] propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec, and comb their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache; it is our nature.

God didn’t make tastes and give men tongues to make them feel guilty for not caring about eternity. He made tastes for tongues so that we would eat and drink what “God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and know the truth.” The apostle Paul figured that Christians would go to dinner parties, sometimes dinner parties thrown by pagans. He didn’t instruct the Christians what to say, he told them what to put on their plate. If there’s a way to hunger for barbecue “to the glory of God,” then certainly there’s a God-honoring way to hunger for knowledge.

Lewis concluded that, not only is the pursuit of knowledge before Heaven and hell permitted, it is mandatory. God doesn’t concede study to us, He commands it. God gifts some to study more deeply but He calls every image-bearer to study devotionally. That is, our reading of both of God’s books—the world and the Bible—should increase our devotion to God. English homework and ethical holiness don’t compete against each other, they inform and activate one another.

The Lord’s commission requires us to make more than converts who profess faith. We are to make disciples who practice faith, here and now, on earth. “Disciple” is not even a good English word. It is a Latin word sounded out for English. The Latin word is discipulus which means student, learner. It’s exactly what the Greek word mathetes means in Matthew 28.

Jesus said, “Teach [disciples] to observe all that I have commanded you.” God made us to be, then saved us to be, then train others to be certain kinds of persons. He created and redeemed us to live a certain way. It is to live—whether thinking, talking, reading, writing, painting, working, playing, buying, selling, mowing, weeding, cooking, cleaning—in such a way that acknowledges Jesus is Lord. This is our confession, something we say. It is also our obsession, something we embody.

Jesus created all things. “Without Him was not any thing made that was made.” Jesus “upholds the universe by the word of His power.” He delights to keep gravity pulling and goats skipping and planets spinning. All true science is the Lord’s; insects and volcanoes and circus animals. He rules over every nation, “having determined allowed periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place” and presidents and trending political hashtags on Twitter. Languages? He is the Word. Numbers and physics and formulas, musical notes and Picardy thirds, logic and literature are all from Him and through Him and to Him.

Great are the works of the LORD,

studied by all who delight in them.

(Psalm 111:2)

We cannot imagine anything lawful that cannot be studied and appreciated and used for His lordship. Imagination itself ought to be sanctified and put to His service. So Lewis said,

[H]uman culture is [not] an inexcusable frivolity on the part of creatures loaded with such awful responsibilities as we.

Everything we do that is done “as to the Lord” is received by the Lord.

None of the above requires a school per se, but this life of discipleship is not different from classical Christian enculturation. We received a way of life under Christ’s lordship and we seek to pass that on. There is a way to talk to adults that pleases Christ, a way to dress, a way to respond when someone kicks a soccer ball in your face, a way to listen and match pitch with the person standing next to you. A school like ECS promotes such a culture.

But the circumstances are not favorable. It used to be that the government legislated the height of the drinking fountain outside the bathrooms, now the government claims authority over who can go into each bathroom. The government, though, is not the biggest problem. Fear and distraction within the church trump all that is outside. Christians have forgotten the cost of discipleship. Christians have dared anyone to make them think, or read, or pay, or die. Troubling things have happened in the shire, not while we were off fighting wizards and orcs and evil, but while we were watching Netflix.

Friends of ECS, you have given us your evening. A team of servants have worked to give you a feast of tastes and sounds and sights. And yet all of us must give up much more. We must give up our lives and “get down to our work.” Hannibal wanted to beat Rome so badly he took elephants over the Alps in winter. The cause of Christ is greater than that of Carthage, and more difficult.

We work “while the conditions are still unfavourable.” We play soccer during recess on a parking lot, but we are thankful that it’s not on a gravel driveway (like we used to). Our part time teachers do not teach for the money, which is good, because we only have baby carrots to dangle in front of them. Many families want this enculturation for their kids but cannot afford it. We have not turned anyone away for financial reasons yet, but we would like for that to always be true.

We have more things to be thankful for than to complain about. God has already grown great fruit in such a young and tiny orchard. Favorable conditions may never come, but we ask some of you to join us, some others to come further up and further in, and some to be encouraged that “in the Lord your labor is not in vain.”

Happy work is best done by the man who takes his long-term plans somewhat lightly and works from moment to moment “as to the Lord.”

Eat, drink, laugh, learn, and give heartily as for the Lord and not for men even without favorable conditions.

These are the notes from my talk for the ECS Fundraising Feast at the beginning of May.